3787

3787 8 December 2022

8 December 2022 admin

admin

A singular story

Within New Caledonia, the history of the colonization of the Loyalty Islands is an exception. Traditionally open to external migration, annexed late by France, deemed unfit for penal or civil colonization, but deeply marked by religious struggles for influence, the Loyalty Islands have developed a unique identity.The oldest indisputable traces of human presence in New Caledonia are currently dated to around 1,100 BC. Exactly where the population and migrations originated is not yet well known. The Loyalty Island tribes are a mixture of Melanesians and Polynesians. Immigrants from the Tonga Islands, master carpenters, Polynesian navigators and Samoan fishermen were included within the chieftaincies due to their skills and knowledge. Ouvéa experienced several waves of Polynesian migration in the 16th and 17th centuries. According to oral tradition, they came mainly from Wallis Island, which is called “Uvéa” in the local language.

The Loyalty Islands were discovered by Europeans in 1793. Raven, the captain of an English merchant ship, was on his way from New Zealand and taking a shortcut to the south when he discovered a group of islands that he named the “Loyalty Islands” for reasons still unknown. According to some historians, the islands earned this name because of the “loyal” character of their inhabitants.

From the start of the 19th century, whale hunters became interested in the rich cetacean resources of the South Seas. From 1810-1820, ships stopped in the Loyalty Islands and the north of New Caledonia’s main island to stock up on provisions and water. A whale oil extraction plant even operated on Lifou. But after 1860 the replacement of whale oil by petroleum and depletion of the pods of whales put an end to this activity in New Caledonia.

The lure of sandalwood attracted Australian traders, and English and American whalers visited the island coasts while they hunted for whales undertaking their annual migrations. These arrivals also became part of the local community which benefited from their technical know-how and keen sense of industry.

The mapping and charting of the Loyalty Islands were carried out in 1827 and 1840 by Jules Sébastien Dumont D'Urville, one of the greatest explorers of the Pacific, who was fascinated by astronomy and natural sciences.

Also in 1840, the London Missionary Society (LMS) sent teachers to the Loyalty Islands to preach the Gospel to the natives and convert them to Protestantism. On 20 December 1843, the French Marist Mission, with support from the French Government and Army, also settled in the islands, to try to convert the natives to Catholicism. The Loyalty Islands then became the often-bloody scene of intense power struggles between Protestant pastors and Catholic missionaries. The conversion to Protestantism of Chiefs Naisseline on Maré (1848) and Boula on Lifou (1851) allowed two LMS teachers, Tataïo and Fao, to settle permanently. Later, in 1856, European pastors settled on Ouvéa.

At this time, the indigenous people used their language and, when necessary, bichlamar, an English-Melanesian pidgin used to communicate with traders and between the various Melanesian peoples. The Protestant missionaries promoted the use of some indigenous languages to bring the Gospel more easily to the island “natives” - as the Kanaks were called at the time: Drehu on Lifou, Nengone on Maré and Iaaï on Ouvéa, while Catholic missionaries preferred French.

The success of the Protestant missionaries explains why the Loyalty Islands still have a strong Protestant majority and why many traditions remain alive (religious, culinary, sociological, words from English in the island languages, cricket etc.).

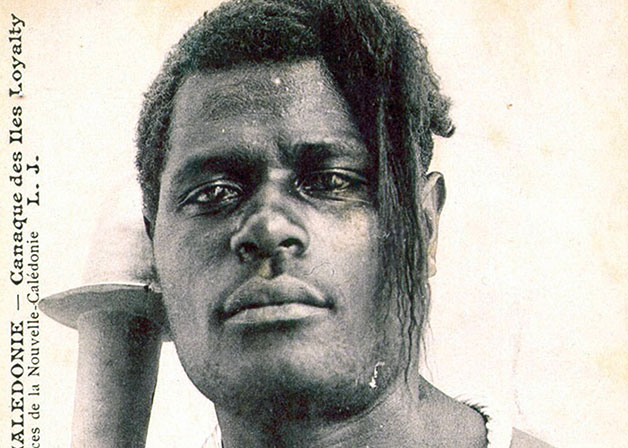

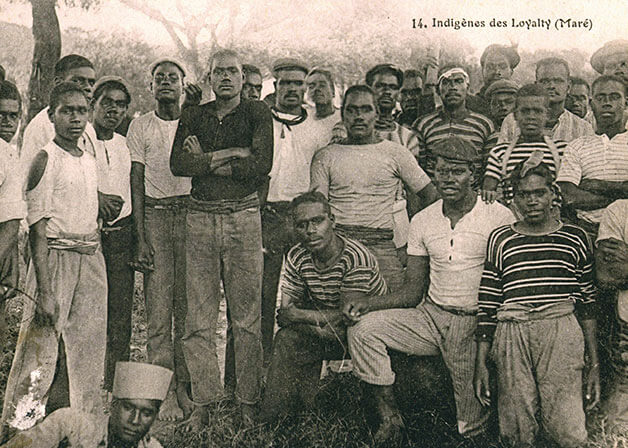

This singular past and the mixed heritage from successive waves of migration have made the Loyalty Islanders “different” Kanaks. The form of their traditional huts — sanctuary and symbol of the clan – bears witness to their dual Melanesian and Polynesian origins, with sometimes a typically rounded Melanesian design and sometimes the square-shaped hut of Polynesian origin. The genetic heritage from intermarriage with European sailors from centuries past can still be seen on the faces of today’s Loyalty Islanders: fine features, light skin and straight hair with blond highlights… Isolation turned them into seafarers, migrations strengthened their sense of hospitality, the fertile land stimulated their agriculture, the religious and political antagonisms strengthened their independence of mind, and flourishing custom traditions united them as a community.